What is lactose?

Lactose is the main carbohydrate contained in mammalian milk.

What causes lactose intolerance?

Lactose intolerance is caused by a deficiency of the enzyme lactase, an enzyme necessary for the digestion of lactose.

Symptoms of lactose intolerance

Symptoms include:

- abdominal pain,

- diarrhea,

- nausea,

- flatulence and/or bloating,

after eating foods containing lactose.

Excluding milk and dairy products from the diet can lead to a treatment.

Lactose intolerance in the population

After infancy, about 75% of the world’s population loses the ability to digest lactose due to a lack of lactase enzyme production and is a natural progression of the body after the first few years. This condition is referred to as primary lactose intolerance.

However, it has been observed that some populations, based on their geographical distribution, are very likely to have the genetic variant that continues to promote lactase production even after infancy. This condition is called “lactase persistence”, and allows the use of dairy products in childhood and adulthood without symptoms.

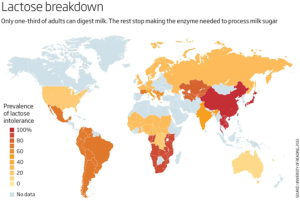

The prevalence of primary lactose intolerance varies considerably by nation. Lactose intolerance is uncommon in populations that consume large amounts of dairy products, such as northern Europeans (10%). In contrast, in the Middle East, about half of the population is unable to metabolize lactose, while in other Asian populations the incidence of lactose intolerance can be very high, even reaching 100%.

Global prevalence of lactose intolerance in recent populations (schematic) map

Types of lactose intolerance

Lactose intolerance can be primary or secondary.

In primary lactose intolerance, the genetic variant that promotes lactase production is missing and abdominal symptoms may occur after ingestion of milk or dairy products.

Secondary lactose intolerance can occur in combination with other bowel disorders such as gastroenteritis, inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease. For example, intolerance may occur in a child after gastroenteritis where the ability to metabolise lactose is temporarily lost due to damage to the intestine and the reintroduction of milk into the diet in a short period of time may lead to further diarrhoea and flatulence.

Screening for primary lactose intolerance

Laboratory testing for lactose intolerance is difficult without genetic testing. It can be checked by performing a hydrogen breath test that calculates the lactose load or by measuring the intestinal activity of the enzyme lactase in a biopsy taken during endoscopy. However, these tests do not distinguish between primary and secondary causes of lactose intolerance and are not suitable for young children.

Lactose intolerance in infants (congenital lactase deficiency) is caused by mutations in the LCT gene. The LCT gene provides the necessary instructions for the production of the enzyme lactase. Mutations that cause congenital lactase deficiency are thought to interfere with lactase function, resulting in affected infants having severely impaired lactose digestion.

In adulthood, lactose intolerance is caused by a gradual decrease in the activity (expression) of the LCT gene after infancy, which occurs in most people. The expression of the LCT gene is controlled by a DNA sequence called a regulatory element, which is found in a nearby gene, MCM6. Some individuals have inherited variants in this gene that lead to prolonged lactase production in the small intestine and the ability to digest lactose for life. People without these variants have a reduced ability to digest lactose over time, resulting in the symptoms of lactose intolerance.

Genetic testing requires a simple blood test. In molecular terms, the presence of one of the genetic variants upstream of the lactase gene promoter suggests that there is persistent lactase production and therefore excludes that the cause of the patient’s symptoms is primary intolerance. The most common variant is C13910T in the LCT gene, and G22018A in the MCM6 gene.

If the genetic variants are absent, the patient may have difficulties in the metabolising milk and dairy products.

Differences between Lactose Intolerance and Milk Allergy

Milk allergy should not be confused with lactose intolerance. Milk allergy can be potentially life-threatening, as it involves an overreaction of the immune system to a particular food protein. When this protein is consumed, an allergic reaction may be triggered. Symptoms can vary from mild (rashes, hives, itching, swelling, etc.) to severe (difficulty breathing, wheezing, loss of consciousness, etc.). Milk allergy can be of two forms, a. direct type allergy mediated by specific IgE antibodies (IgE-mediated) and b. a slowed-down type of reaction that is not mediated by specific IgE antibodies (Non-IgE mediated). Immediate-type allergies are characterised by the onset of symptoms within the first 48 hours, while in slow-type allergies symptoms start after 48 hours. Often, slow-type allergic reactions are mislabeled as intolerance symptoms, using the terms “lactose intolerance” or “milk intolerance”.

|

Lactose intolerance |

Allergy to milk ΙgE – mediated | Allergy to milk Non-IgE mediated | |

|

Symptoms |

Only gastrointestinal symptoms: pain, flatulence, diarrhoea |

Skin, respiratory and gastrointestinal – symptoms of anaphylaxis or other systemic allergic reactions |

Dermatological and gastrointestinal |

|

Mechanism |

Non-immunological. Reduced ability to digest lactose |

Immunological mechanism mediated by specific IgE antibodies |

Immune mechanism mediated by specific T lymphocytes |

|

Clinical diagnosis |

Low lactose exclusion diet leading to symptom improvement and then reintroduction with symptom relapse. There’s usually an improvement within 48 hours of the exclusion |

Milk protein exclusion diet leading to improvement of symptoms. Reintroduction is not recommended unless a full clinical and laboratory examination is performed because there is a risk of anaphylactic shock. Skin tests – prick tests by an allergist and Clinical Challenge |

Milk protein exclusion diet leading to symptom improvement and then reintroduction with symptom relapse. It may take 4-6 weeks for symptoms to improve. Skin tests – patch tests by an allergist |

|

Laboratory Diagnosis |

Gene testing |

Specific IgE immunoglobulins, Basophil Activation Test (BAT test) |

Lymphocyte transformation test (LTT test) |